The Price of Freedom

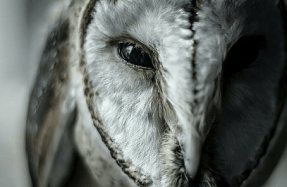

Photograph by Clay Gilliland, Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Clay Gilliland, Wikimedia Commons Christina Kim grew up in western North Korea, in a town where modest houses were attached and stood in a row. “If your neighbor farted, you could hear it,” Kim said. She lived with her parents and two siblings in the province of North Pyongan, reportedly a major military industrial area. Kim’s father worked in a munitions factory that produced chemical weapons. He often complained the factory was full of respiratory diseases, and he worried that the work—the details of which he could not disclose to his family—was shortening his life. (“Christina Kim” is a pseudonym; much about her story can be dangerous to loved ones in North Korea, even today.)

The family’s seongbun—the caste-like system that classifies North Koreans based on their political, social, and economic background—was average. Kim’s father eventually secured a place in a migrant worker program in Russia as a logger; all his income went back to the regime, and the family soon fell on hard times. Kim’s mother moved her children to a village where their grandmother lived, near the Paektu mountains. The mountain chain contains the tallest peak in North Korea, considered by some to have mythical qualities. It was so cold there that families built fires most months of the year.

Each morning, when the adults went to work for the regime, the children stayed home, warmed by coal. One day, a house nearby caught fire, with a boy inside. Kim watched the father race into the house and emerge with his most valuable possessions: a portrait of then-Supreme Leader Kim Il-Sung and another of his first wife, Kim Jong-Suk. The child never came out.

At the time, Kim believed the man’s actions were valorous, and that prioritizing political iconography over his own child’s life was just and good. She also understood that speaking ill of the regime could end in death. By then, Kim knew an old saying, “one ends a long life because of a short tongue.” And, so, she came to accept that one day her body, too, could—and ought—to be sacrificed, should the Leader require it. Perhaps, she thought, her father would abandon her in a fire, or maybe hers would be one of the homes a black car would visit to take her family to a prison or re-education camp, never to be seen again.

Each day at school, the students bowed to a portrait of Kim Il-Sung. “Always ready,” they chanted in unison, indicating their loyalty and preparedness to sacrifice their lives. After she attended university, Kim became a kindergarten teacher and taught her students what she’d memorized years earlier: Kim Il-Sung’s birthday, known as the “Day of the Sun,” and how to sing gospel-like songs as a form of worship. “I used to look up to Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il as my gods,” Kim said.

By the time Kim married and had children of her own, her gods had largely stopped providing salaries and food rations. Kim begged her parents for food to feed her

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days