Shooting Up

VISHAL THAKUR’S CLOTHES hung off his gaunt body. He did not have the means to satisfy the demands of his hollow belly, and could not bring himself to ask the family he had alienated for help. Friends had dropped out of Vishal’s life when they realised that he was deaf to their pleas to get his life together. Neighbours whispered “nashedi”— junkie—when he lumbered past on the forested roads of Shimla. Thakur was in his early twenties back then, and had already been dependent on a cocktail of psychoactive substances for a decade—alcohol to begin with, at first covertly stolen from his father when he was not yet a teen, then bhang, opium, smack, assorted over-the-counter no longer able to move, a passerby handed him twenty rupees. He used the money to get high. Food could wait.

Anxious young men in the main room of the Moksha Foundation clung to Thakur’s every word as he narrated his story. Thakur is no longer the desperate, dishevelled boy he was describing. Today, he is the head of Moksha, a private de-addiction centre that caters to those with the same affliction he once suffered from.

Thakur was pulled from addiction’s iron grasp 13 years ago, when he was 28 years old, after a former drug user, Sandeep Sood, forced him to attend a Narcotics Anonymous meeting. Sood is pills, cough syrups, amphetamines and prescription opioids. The only community he had left consisted of other drug users, whom the good and normal townspeople of Shimla wanted nothing to do with.

After days of hunger, Thakur found respite at the langar in Shimla’s largest gurudwara. He ate as much as he could, and crammed his pockets with rotis for later. On his fourth consecutive day getting a free meal, he was kicked out and told to get help. He began to starve again. Pain and sweating marked the onset of a different hunger—the desperate craving for a rush. Paranoid and weak, he stumbled around the city. When he collapsed, now Thakur’s right-hand man at Moksha. “I don’t remember those two years of my life, 26 to 28,” Thakur told the room. “It’s missing.” After going clean, he reintegrated into society—he now has a wife and children, and his only vices now, he said, are the occasional cigarette and qawwali, which he sometimes stays awake listening to till three or four in the morning.

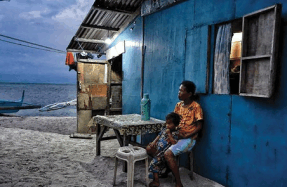

Moksha’s main room, which doubles as its office, overlooks the Ghanahatti valley on the outskirts of Shimla. When I visited last summer, the dry pines that covered it shone golden under a strong sun. Dressed in a shirt, glasses slightly askew, Thakur sat between his wife and Sood on a grey velour couch as his six-year-old son ran around a table clutching a spoon.

Moksha is one of the largest private de-addiction centres in Shimla, the capital of Himachal Pradesh. Most of its concrete walls are bare and unpainted, and rebar juts out from the rooftop of its only building, where Thakur housed a flock of cooing white pigeons—a personal hobby. Until four years ago, Moksha’s main clientele were alcohol users. But the main “DOC”—drug of choice—has since changed to chitta: an umbrella term for heroin and a variety of adulterated opioids. The first chitta-dependent client walked into Moksha in 2014. After that, Thakur said, “I knew from how many started coming in that it would be a problem. I understood that it would increase.”

Himachal Pradesh is one of many states in India’s north and north-east where the numbers of dependent chitta users and peddlers are rising faster than crime or health departments can handle. Moksha houses between forty and sixty users at any given time, though the number dropped to roughly twenty following the COVID-19 lock-down. Last July, it had 47 residents, 36 addicted to chitta. A disproportionate number were adolescents—some barely into their teens, still acned and with only the first whispers of facial hair. Some had relapsed. One emaciated 13-year-old in a ratty shirt had

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days