Reconstructing Violence

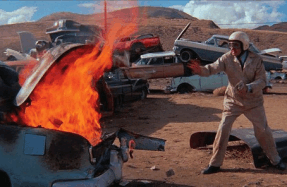

There’s a point in nearly every Nicolás Pereda film when the narrative is either reoriented or upended in some way. In the past this has occurred through bifurcations in story structure or via ruptures along a given film’s docufiction fault line. Pereda’s ninth feature, Fauna, extends this tradition, though its means of execution and conceptual ramifications represent something new for the 38-year-old Mexican-Canadian filmmaker. Following a decade working at the intersection of fiction and documentary, Pereda has, in recent years, mostly forgone the aesthetics of nonfiction in favour of a unique form of narrative cinema in which real-world issues and anxieties are couched in forms at once grave and fantastical. In the medium-length films Minotaur (2015) and My Skin, Luminous (2019, co-directed by Pereda’s longtime lead actor Lázaro Gabino Rodríguez), Pereda refracted ideas related to storytelling, rituals, and pedagogy through an oneiric lens that quietly conjured a kind of hallucinatory social drama bereft of the simplicity and didacticism that tends to mar such culturally conscious cinema. Less dreamlike but equally imaginative, Fauna charts a sidelong course around one of Mexico’s more pressing sociopolitical concerns—the impact of narco culture on Mexican society and its troubling representation in the media—by situating its characters within a subtly expanding dramaturgical framework in which notions of performance and identity are made to blur and reanimate as the narrative shifts between the quaint and the cryptic.

Carefully composed but unassuming, the film’s opening moments suggest something far more mundane than what eventually takes shape. Through the windshield of a moving car, cinematographer Mariel Baqueiro’s camera peers across a hilly expanse, all dusty slopes, winding roads, and vanishing horizon lines. Somewhere in the north of Mexico, thirtysomething partners Luisa (Luisa Pardo) and Paco (Francisco Barreiro) are making the slow trek to a remote mining town to visit Luisa’s parents. On the way there they’ll meet Luisa’s estranged brother, Gabino (Rodríguez), in an affable but awkward encounter that hints at the strange family dynamic that Paco will be forced to navigate—particularly when Luisa’s father (José Rodríguez López) learns that Paco is an actor with a recurring role in a narco-themed television show. Following a wonderfully embarrassing introduction in which an unwitting Paco buys the local market’s last pack of cigarettes off his host for 100 pesos to give to Gabino, the characters gather at the family is a resolutely sly and humorous film, especially in these introductory scenes where the chemistry between the actors—all veterans of Pereda’s cinema—is free to spark in moments of both casual conversation and unspoken discomfort.

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days