“I know it is a great metaphor, but a metaphor for what I could not say.”

—Werner Herzog in his recent memoirs about the steamship hoisted over a mountain in Fitzcarraldo (1982)

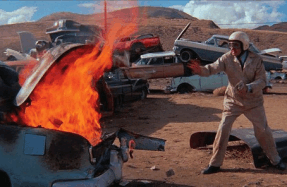

Making a deserved victory lap on the festival circuit around the time of his 80th birthday in September 2022, the ever-prolific and internationally popular Bavarian filmmaker Werner Herzog, eager to prove that he is not resting on his laurels, came with an entire package of new works in tow, as well as an exhibition of material from his personal archive presented at the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin. There were not one, but two films: The Fire Within: Requiem for Katia and Maurice Krafft (2022), drawn mostly from footage shot by the two eponymous volcanologists before they met their grisly fate in a pyroclastic flow emerging from the active volcanoes on Mount Unzen in Japan in 1991, which is another addition to the ever-growing cycle of Herzog films structured around “visionary” imagery, often captured on expeditions to extreme landscapes; and Theatre of Thought (2022), which explores an interior landscape— the human brain—in typically iconoclastic Herzog fashion. While Herzog has always insisted that the awesome yet horrible mystery of the external territories explored in his filmography correspond to inner states, Theatre of Thought belongs to a more prosaic strand in his work, in which conversations with experts on a subject are intercut with footage, some of it stylized or at least slightly surreal, in a way that showcases some of the theses and themes explored—not necessarily in the way his subjects might interpret them, but rather how Herzog wants them to be seen.

Additionally, there were two new books, whose genesis was probably facilitated by lockdown necessities. (These pandemic restrictions applied even to Herzog, who proudly recounts how on a visit to NASA the CEO recognized him and allowed him unprecedented access: “Let the madman with the camera in!”) Herzog has insisted repeatedly that what he thinks will really endure of his work is his writing, not the movies, but that may be part of his self-stylization as a man who rarely watches cinema. Admittedly, compared to the more than 70 films of varying length he has made since his short debut, Herakles (1962), Herzog’s written output may seem paltry, though he considers his scripts as literary emanations waiting to be transformed through the process of filming. But arguably, prose like Of Walking on Ice (first published in 1978)—about his three-week walk on foot from Munich to Paris during winter to “save” his friend, ailing film historian Lotte Eisner—and Conquest of the Useless (2004), which describes the notorious production of Fitzcarraldo, are among the most pungent expressions of what makes Herzog Herzog.

The same goes (partially) for his most recent two publications, the first of which, like , is almost archetypal in its Herzogness, and certainly conjures a is a slim volume recounting the story of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese soldier who kept defending a small island in the Philippines for 29 years after the end of World War II. It is billed as Herzog’s first novel, even as it bears the laconic (and characteristically Herzogian) inscription: “Most details are factually correct; some are not.” The other volume is a memoir named , titled after the classic Herzog film released in English as (1974) In the foreword, Herzog notes of the film’s original title that “almost nobody was able to reproduce it correctly. I am making a second attempt here.” That attempt may also be considered a populist gesture by Herzog, clearly catering to a wider audience that may be more familiar with his established persona than with his work as a filmmaker.