The voice of the people

Visit Prague for the opening night of the opera season and you might catch Smetana’s Libue. Visit Moscow, and it might be Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar. And in Warsaw, Halka by Moniuszko. But if you never visit the Czech Republic, Russia or Poland, you are unlikely to see any of them. In the increasingly cosmopolitan world of classical music, the ‘national opera’ is an unusual phenomenon – an artistic statement of independence, vernacular in both music and text.

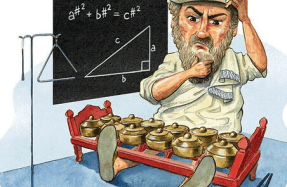

Most national operas date from the late 19th century, a time when empires across Europe were losing their cultural authority and occupied nations were beginning to assert their identity. Opera proved an ideal medium, with words in the native language and music drawn from the country’s folk songs and dances. By the early 20th century, the trend had spread beyond Europe, as far as Azerbaijan (Leyli and Majnun by Uzeyir Hajibeyov) and even Argentina (El Matrero by Felipe Boero), ensuring local colour as opera traditions developed around the world.

Glinka’s was the first national theme, a hymn of praise sung in the Epilogue when the Tsar makes his triumphant entry into Moscow, became virtually a second national anthem in Russia later in the century.

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days